Disney’s live action remake of The Little Mermaid is getting decent reviews from domestic audiences, although its lackluster performance overseas, especially in China, signal that it’s unlikely to break even. But while even many critics of the movie are praising the performance of the titular actress Halle Bailey, the decision to recast a role filled by a white, red-haired character in Disney’s 1989 animated version with a Black actress has led to a racist backlash from ethno-nationalist pundits in both America and abroad.

As I wrote several years ago, having a Black actress play the Little Mermaid provides an immediate physical signifier of ethnic “othering” that makes perfect historical and artistic sense. Indeed, black skin in the 21st century performs a similar function as that played by red hair in the 20th century.

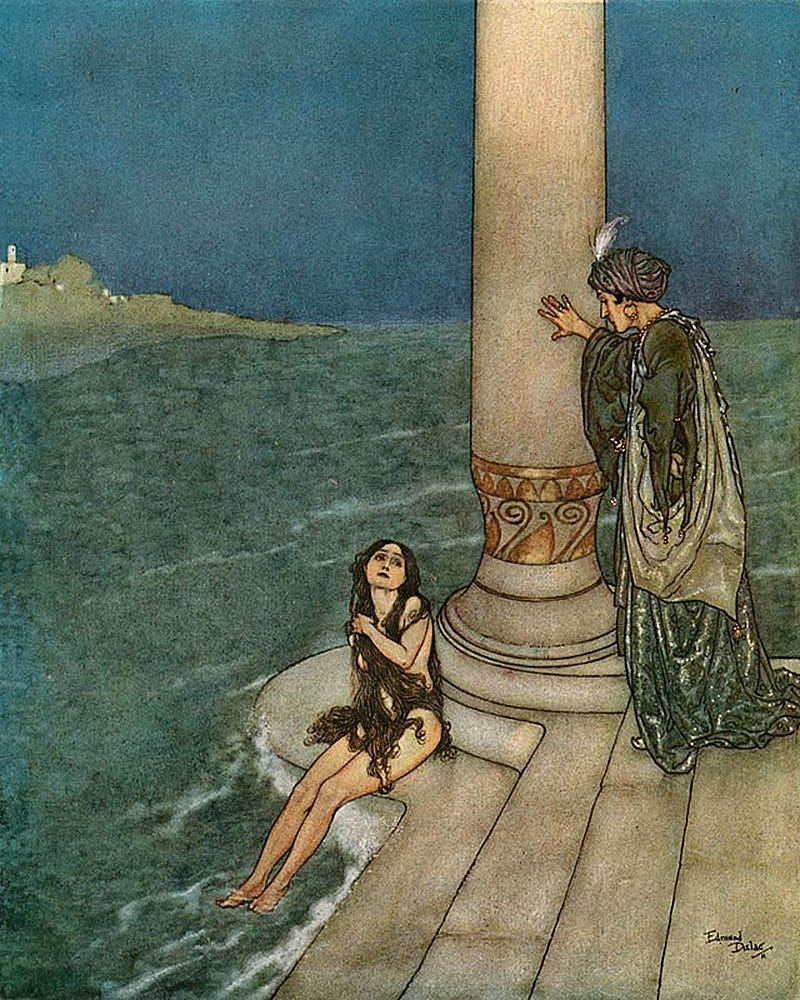

First, it’s worth noting that giving Ariel red hair was as arbitrary a decision as going with a Black actress. Hans Christian Andersen never specified the Little Mermaid’s hair color, and early drawn depictions show her with dark hair.

Disney had originally intended to make the 1989 version a blonde, but the animators worried that it would make her look too much like Darryl Hannah’s nude mermaid in the adult-focused 1984 movie Splash. But while Disney acted out of pragmatism, here’s why casting a red-haired Little Mermaid in 1989 was an unintentionally clever decision.

Red hair has lingered in our cultural memory as a marker of ethnic otherness that has its roots in two centuries of often virulentanti-Irish prejudice. That prejudice was once so intensive that in the 19th century the Irish were not even considered fully white. They were often depicted in newspaper cartoons with distorted physical characteristics that emphasized their racial otherness (and which were often accompanied by ethnic stereotypes about a lack of cleanliness, work ethic, and self-control).

Irish-Americans had to fight for cultural acceptance over the course of generations, though in the 19th century they often did so by violently repressing free Black workers. I might not have a Mayflower pedigree, or so the Irish-American working man thought, but at least I’m not Black.

By the mid-20th century, anti-Irish prejudice had begun to taper off as Irish-Americans built thriving communities (and successful political machines) in major cities like Boston and Chicago. But one artifact of those old prejudices lingered on: suspicion of red hair. While the gene for red hair is widely distributed across Northern Europe, it is most visible among the Irish, Scottish, and Welsh, with 10% or more of their populations having red hair. Red hair was considered exotic in America in the nineteenth century, both an object of fascination and repulsion.

And the old ethnic stereotypes that had been affixed on immigrants from these countries were then ascribed to all people who happened to have red hair. For example, orphans with red hair once had more difficulty finding adoptive parents than their tow-headed counterparts because of the widespread assumption that redheaded kids had bad tempers and were prone to violence. Whether on a conscious or subconscious level, red hair evoked Celtic ancestry, which signaled ethnic otherness, marginalization, and a general sense of not belonging in respectable society.

Some sense of that meaning persists even today, like calling someone a “red-headed stepchild” to signal that someone is unwelcome or uncouth. And it is no accident that the titular hero of Little Orphan Annie, first published in 1924, was given vividly red hair. Doing so reinforced the point that her situation was unusual, that not only do millionaire war profiteers not adopt many children, they especially don’t adopt redheaded ones!

The 1920s are also when Walt Disney started his career, with his first animated film in 1923 and the creation of Mickey Mouse in 1928. The Walt Disney Studio was formed in a milieu when red hair was still a visual shorthand for Irish exclusion. That inherited cultural memory would become less intense over time, but through the mid-20th century it capably performed its role of signifying cultural distance between the character with red hair and the rest of society.

And having red hair evoke even a vague, subconscious sense of cultural alienation in the minds of the audience fits the character arc of most Disney protagonists. One standard Disney storyline is that of an outsider desperately seeking approval, failing temporarily, before discovering that they possessed heroic attributes deep down inside all along.

Take Ariel from the Little Mermaid. She yearns to be “part of your [land-lubber] world” but she lives in the sea and has no legs. If you’re the one in charge of her animation design, what visual signifiers could you use to make your audience look at her and automatically think outsider? Oh yeah, red hair! Redheaded people are unwanted, don’t belong, are rebellious, and they make great mermaids. (Although, as medieval illuminations show, mermaids came in many shapes and hues.)

Red hair was also a useful external signifier last century because it had lost some but not all of its charge. Redheadness had become a relatively benign category of alienation by the late 20th century. Using red hair in the nineteenth century would likely have provoked antipathy or even revulsion for non-Celtic audiences, but by the twentieth century the popular reaction had been softened to something closer to sympathy.

Today, true Irish-American exclusion has mostly passed from living memory. Red hair no longer carries the same artistically-evocative cultural baggage it once did, or at least not nearly to the same extent. (Though it lives on to some extent in the UK.) If you’re an animation studio, what’s another visual signifier of cultural alienation that might serve as a replacement for red hair? It needs to be something that most folks will instantaneously see as a traditional marker of exclusion, but it also has to be relatively benign today compared to a generation or so ago.

It shouldn’t take a mermaid (or merman) to catch my drift. In the early 21st century, black skin functions as a more effective physical signifier of cultural alienation than does red hair. While structural racism persists and white supremacy has seen a resurgence in recent years, overt racism is not as powerful as it was half a century ago. That means black skin is not so powerful a physical signifier as to evoke repugnance or dismissal in white audiences (as it would have for too many in the early and mid-twentieth century), but it is not yet so benign as to lose its ability to signal otherness in a society which remains racially unequal and divided.

Indeed, to return to our adoption example, just as the New York Times once worried about the difficulties of placing redheaded children in adoptive families, today demand for white adoptees is higher than for Black adoptees. As Kimberly Jade Norwood puts it, “In the adoption market, race and color combine to create another preference hierarchy: white children are preferred over nonwhite.” When Sony Pictures released a new film version of Annie in 2014, replacing the redheaded Annie of the 1920s with Quvenzhané Wallis, it was simply a realistic reflection of the changing cultural and racial mores of America in the intervening century.

So, next time you hear an announcement about yet another traditionally redheaded character being played by a Black or other minority actor, realize that doing so is a reasonable artistic decision with strong historic precedent that will help audiences automatically pick up on the core themes of the narrative. Indeed, recasting may more accurately reflect the originally intended ethos of the character regardless of what that character once looked like.

This material is adapted from my article on Libertarianism.org.

Oh, and using the term "virtue signaling" is absolutely a value judgement. It carries negative connotations. It implies insincerity and artificiality. It's a way of diminishing someone's choice. Have you ever seen it used in discourse in a non-negative way? I sure haven't.

I think we're arguing over trifles. Intent doesn't really matter much. Red hair was an intentional choice for Little Orphan Annie but not for the (1989) Little Mermaid. Black skin was an intentional choice for the (2023) Little Mermaid. What matters is how audiences *receive* those physical signifiers. And the overreaction from racists is a pretty good sign that the reception is doing something!