America Wins the Olympics Without Really Trying

Underperforming our max potential is, paradoxically, a sign of our strength

As I started writing this, China led the USA in Olympic gold medal count by one (although lagging considerably in silver and bronze). China might fall short in the final count, but if they do hold that lead, there will be much Discourse™ about it as a sign of American weakness / Chinese strength. There’s political utility to be extracted from that failure, whether by China hawks or anti-woke agitators. Nationalists, funnily enough, love stories of national decline because it lets them say, “See, you need us.”

This is hardly novel. Those of a certain age will remember the way Soviet bloc triumphs over the USA at the Olympics in the 1970s and 1980s fed into a popular narrative of Communist rise and American decline. After all, their nuclear arsenal was larger than ours, their economic growth rate unparalleled, and, adding insult-to-injury, even their puppet regime in East Germany was consistently beating America at the medal table! Americans might still be richer and freer —or so the story went—but we were soft, lazy, and weak. The future was not red, white, and blue; it was just red.

That sounds funny today given that Russia hasn’t been a contender for the top of the medal table for decades. At the 2016 Rio Olympics, even a combined Russia and unified Germany had fewer medals than the USA. But the rhetoric of Olympian decline could conceivably make a comeback for the foreseeable future should China continue its rise in the Olympic rankings.

But either way, optimizing for success at the Olympics requires creating institutions that are, paradoxically, a signal of political economic failure. State support for Olympic hopefuls housed at centralized sporting schools can indeed boost medal counts, but that requires a kind of singular obsession with performative national greatness that is the antithesis of a truly free and prosperous society.

The simple truth is that pursuing Olympic glory is unprofitable. A handful of medal-winners with sympathetic story lines may have a shot at winning significant endorsement deals, but most athletes receive little to no financial compensation in exchange for being faster, higher, and stronger than regular human beings. While a few Olympics events overlap with professional sports — eg, basketball, handball, etc — most do not, meaning that many high caliber athletes naturally self-select out of the Olympics pipeline. There’s a reason Jason Kelce, for instance, played professional football rather than becoming a shot-putter or weightlifter.

Countries with strong state capacity — and especially those with authoritarian governments — are able to exploit the athletic deadweight loss to professional sports by creating state-run academies and by directly subsidizing athletes for staying in those unprofitable sports.

You might consider this a way of correcting a market failure; however, that assumes that diverting athletic talent away from the sports that people actually want to watch most of the time isn’t the real failure. I myself would much rather watch the Kelce bros on the football field sixteen times a year than once every four years at the Olympics competing in a sport that I routinely forget exists.

Regardless, state support for athletes can work wonders. East Germany, with a population of just 16.4 million in 1988, won more medals at the 1988 Seoul Olympics than the US with a population 15x larger! Of course, that success was built from an invasive system of surveillance, control, and abuse. Every young student was tested for athletic ability; those with the most talent were conscripted into sportschule, state-run sports academies. These student-athletes, some as young as five years old, might only see their families infrequently and were force-fed steroids. Sure, they achieved Olympics glory, but at what human cost? Those medals were an indictment of the abusive system concocted to produce them.

While China’s system is not quite as rigid as the East German one — although the mass doping scandals are a through-line — it does spend $3.2 billion on a network of sports academies that focus on arbitrage opportunities in sports featuring “small, fast women, water, and agile” athletes. By contrast, the US government contributes nothing directly to the primary US Olympic programs, which have total budgets that are only about a tenth the size of China’s spend.

Ultimately, however, that spending is an attempt to keep up with the Joneses. There is a strong correlation between per capita GDP and medal count. (See below.) The US is the wealthiest large country in the world with a 5x higher GDP per capita than China. Thus far, that has been enough to make up for the disadvantage of having less than 4x fewer people.

We are so rich that even our middle class can afford to pursue sports on a non-professional basis. A champion like Simone Biles is at the top of pyramid of many thousands of middle-class American households taking their little girls to the local gym for practice, driving to competitions on the weekends, and ultimately organizing their entire life around the pursuit of a niche sport. With the exception of crossover sports like basketball, the Olympics feature a bunch of actual American amateurs competing against state-sponsored semi-professionals.

This isn’t to say that the state doesn’t play any role in the creation of America’s Olympic talent pipeline, especially in regards to the exceptional performance of America’s female athletes. After Title IX was finally applied to college athletic departments in 1978, the number of female college athletic programs soared; the new demand for college female athletes — and supply of scholarships — then ignited a flashover effect on participation in high school sports, which saw an incredible 840% growth between 1971 and 2002.

Functionally, this amounted to a government-mandated financial transfer from profitable, mostly male programs to mostly unprofitable, female athletic programs, although that calculus has since changed. (Male athletes are also more likely to be siphoned off into medal-lite professional sports like football or basketball and out of medal-heavy sports like swimming and gymnastics.)

The results speak for themselves. America’s female Olympic athletes now consistently win more medals than their male counterparts. For example, of the 46 gold medals won by the US delegation at the 2016 Rio Olympics, 27 went to female athletes (plus 1 to mixed tennis doubles). At the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, it was 23 of 39. This year, as of August 8th, it’s an incredible 19 of 30 gold medals (plus 1 for a mixed swimming relay). We’ve become used to America’s female Olympians bringing home 60% of our gold medal haul; by contrast, in 1972, America’s female athletes won less than a third (10 of 33).

But what is incredible about America’s university-based Olympic pipeline is that we don’t gate it. This is fundamentally different from most other Olympics programs; it’s impossible to imagine, for instance, an American joining an East Berlin gymnasium in the 1980s in order to train to compete under a US flag. (Unless, that is, they defected first.) Yet our intercollegiate athletics don’t just train America’s Olympic medalists; our schools train our competition as well!

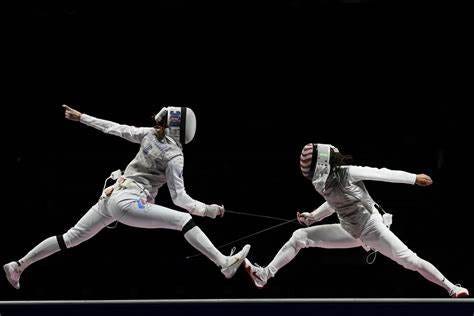

Consider fencing, in particular epee and foil. Of the twelve individual male and female medalists at the Paris Olympics, only three medals went to Americans. Yet of the remaining nine medalists, four fenced while enrolled at US universities, including Notre Dame, Stanford, and even Long Island University. In other words, the US might only have won a quarter of the medals, but we trained more than half of the world’s champion epee and foil fencers!

Here is where the American political economy truly shines. Sure, if all you care about is enhancing a narrow, blinkered vision of national prestige, then a top-down, State-supported sports regime can deliver the goods, albeit at a high cost to the individuality and health of the athletic cogs in your jingoistic machine.

But America’s college-based Olympic pipeline — marked by decentralization and competition — isn’t bounded like other, expensive, nationalized sports programs. Our universities welcome athletes from all over the world, helping them to perform to the best of their individual ability, regardless of the way it might impair the Olympic prospects of American-flagged athletes. And in doing so, it elevates the entire global community of athletes. It more truly gets at the spirit of the games, the desire to unite the world behind the constant pursuit of citius, altius, fortius. U-S-A! U-S-A!

Great research here and summarizing an important juxtaposition of approaches. Thanks for putting this together!