Data is Better than Oil; It's Information

Misunderstanding the difference between data and information.

“Data is the new oil.” At this point, comparing digital data to petroleum is cliche and a constant annoyance to digital policy wonks, who release piece after piece rebutting the overly simplistic and yet durable comparison. Unlike oil, data is non-rivalrous, non-consumable, and becomes more valuable with use. (I myself entered that particular skirmish myself with a podcast comparing data to guano, although even that comparison is fraught).

But the idea remains popular because it fits into a pre-existing narrative with which the general public is familiar. Everybody knows that oil is valuable, that we need(ed) it to run our cars, that it turns poor desert countries rich, and that massive oil producing corporations comprise a Big Oil semi-cartel. In the public imagination, oil = $$$.

It’s easy to transpose that familiar framework onto the digital economy. Everybody knows that data is valuable, that we need it to run our social media networks, that it turns college dropouts into the wealthiest people in the world, and that Big Tech has remarkable global reach and domestic political influence.

But the similarity stops at the surface and upon digging down it becomes obvious that the “stuff” we’re comparing—the decayed dinosaur goop and the 1s & 0s—is fundamentally different. The oil metaphor leads people to think that data is a thing they already possessed but which is taken from them, stolen even, by greedy Big Tech behemoths much in the same way that oil is extracted from the ground often regardless of the wishes of the locals.

Yet that’s simply not what data is. Even Joe Biden misunderstands what data is! Your data might exist prior to digitization, but if so it exists in a fundamentally useless or, at least, undervalued state. Its utility is locked away, accessible only by you and perhaps a limited circle of people around you. As such, it has highly limited value.

Digitization unlocks additional value from your data. It does that by lowering the barriers to exchange and use. It makes data more widely accessible by making it cheaper to access, making it, seemingly paradoxically, far more valuable. Cheap data is valuable data.

The terminology I use is that digitization refines low value data into high value information. If data is the basic commodity, then information is the finished good. Digitization allows each piece of our data, every little factoid, to be aggregated into a whole that is more valuable than the sum of its parts.

Consider the following example. The longer you live somewhere, the better you learn its topography. You know which is the fastest route to get to the Costco at 2pm and which is fastest at 5pm. You know not to drive towards the university campus on football game days. You saw the cops set up a speed trap on your way to work, and so call your friend who commutes the same way to tell them to watch out.

But in a pre-digital age, that data was limited in value; its use restricted only to you and people you knew personally. Digitization allowed that data to be pooled with other people’s data, creating a dataset with vastly increased utility and value. Sure, you knew that traffic is particularly bad on Woodruff Road during rush hour, but thanks to the data uploaded by a fellow driver—a complete stranger to you—you also know that your plan B route is backed up thanks to an accident. Better pick a new path, a plan C, one that you don’t usually take but which other drivers do and report being clear.

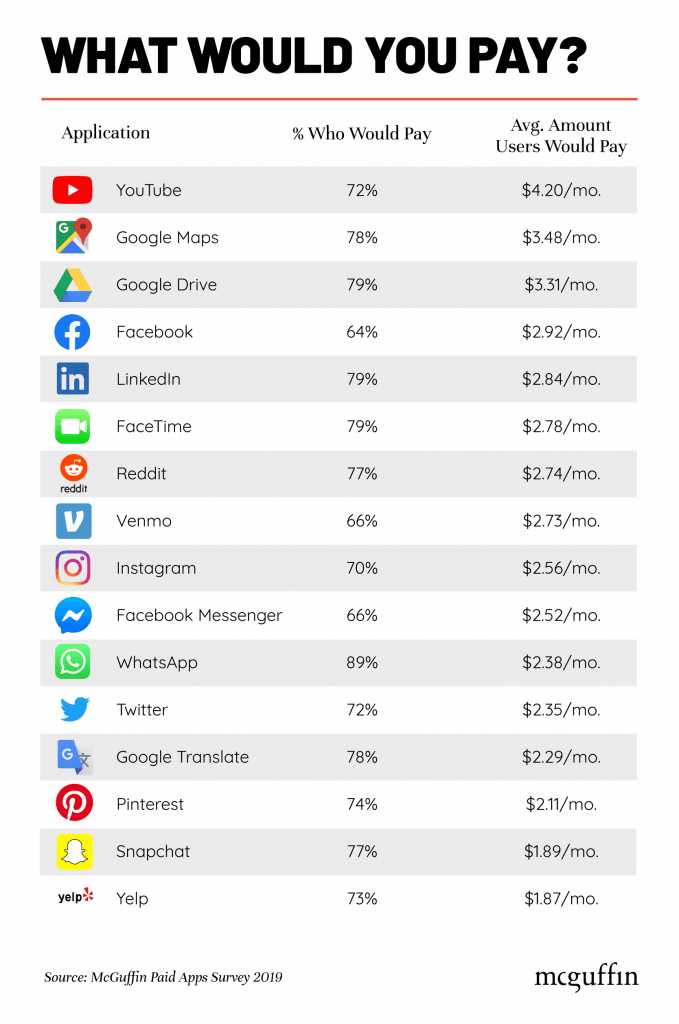

When our data is combined it enhances the utility everyone extracts from that data. Every piece of data improves the value of every other piece of data in a virtuous spiral of refined information. And that information has real value. Indeed, mapping apps are the second most valued product of aggregated data, behind only Youtube.

The average person reports they’d be willing to pay $3.48 a month, or just over $40 a year, for access to Google Maps. (Note that this is the surveyed result; it’s possible that people’s revealed preference would be even higher, especially given that alternative mapping software exists.) But, functionally speaking, people think they’re at least $40 a year better off than they were prior to the digitization of our local knowledge of where we live.

And that’s merely a single aspect of the data-to-information pipeline. The same thing has happened with networking, visual entertainment, encyclopedias, photo-sharing, and so on.

To turn to the theoretical, those of you who have read Friedrich Hayek might recognized the contours of a knowledge problem, based in his observation that knowledge is distributed while decision-making is often centralized. But central authorities simply lack the local knowledge needed to efficiently and effectively coordinate action. It’s one reason why command economies tend to simultaneously overproduce goods that few want while underproducing goods that they need.

Hayek’s solution to the knowledge problem was to devolve authority as much as possible, empowering those with local knowledge to make local decisions. Economist Elinor Ostrom famously won the Nobel Prize in Economics for applying that insight to resource management.

Fascinatingly, digitization partly solves—or perhaps the better word is “mitigates”—the knowledge problem. An online platform gathers and refines our localized data and turns it into a centralized database that enables better decision making. There are still limits on how far this mitigation extends, and it’s notable that governments drastically lag private platforms when it comes to operating such data-to-information pipelines, but the fundamental limits of the individualization of knowledge have been pushed back once again. Just as the telegraph once allowed greater access to local knowledge, so too does digitization, albeit on an even grander scale.

But while data-to-information unlocks value, I’d like to point out that it can also create a fundamentally different product than the data it started with. It’s not just data + data = value-added dataset, though that’s certainly true. It’s that the basic thing under discussion may be transformed.

Consider the photo your cousin snapped with an old school film camera and then shared on Facebook or Instagram announcing the newest addition to their family. It’s easy for people to think of the uploaded photo as merely a digital substitute for the actual, printed photo of that little baby; indeed, it’s likely even an *inferior* substitute with lower resolution than the original pic.

Yet think about the purpose behind uploading the photo: sharing. They wanted everyone they know to see their kid and share in their delight. Hundreds or even thousands of people can look at that digital photo instantly. By contrast, in ye olde pre-digital days, a family would have to go to the photo processing lab, have all those additional copies printed, buy postage and envelopes, go through their address book, and then mail the pictures out, where days later the photos finally reach their recipients.

In other words, that digital photo is not inferior at all to the original but dramatically superior! It substitutes not for one picture but for a stack of hundreds of pictures. Comparing it to the original is comparing apples and oranges. And distributing that photo is now both exponentially faster and cheaper. The finished digital product bears literally only a surface resemblance to the physical piece of data it replaced. One could add up the financial cost of the envelopes, stamps, time spent addressing, etc to find the monetary value that has been added, but we intuitively know that it’s worth quite a lot.

That’s enough for today. In my next post I’ll discuss why the difference between data and information ought to change the way we talk about data privacy.