(Not) Bob Jones University

Drama at the World's Most Unusual University

A student fashion show inspired by Paradise Lost brought down the mandolin-strumming president of a college that once billed itself as “the World’s Most Unusual University.”

There’s a lot to unpack in that sentence. As both a historian of 20th century religion in America and as an alumnus of Bob Jones University, I’m somewhat uniquely qualified to walk you through the ultimate causes of the late unpleasantness.

The imbroglio began with a student fashion show in December 2021. For his capstone project, fashion design student Matthew Foxx had put together a runway show that thoughtfully explored the story of the gospel as embodied in renaissance era clothing. For example, a crown-of-thorns haloed model strode the cat walk wearing a coat stained blood red, a visual representation of a crucified Christ who, in Foxx’s words, “covered our sins…completely and fully like a wrap coat covers the body completely and fully.”

But many in the network of fundamentalist pastors that are a major pipeline for incoming BJU students viewed the display in less metaphorical terms, calling it “blasphemous,” “gross,” “too feminine,” and “what happens when Christians ‘model’ their college programs after those of sodomites.” Facing widespread queer panic among stakeholders, university President Steve Pettit put out a statement condemning the show as “clearly sacrilegious and blasphemous.” But the statement came too late, and with inadequate brimstone, to appease the hardliners.

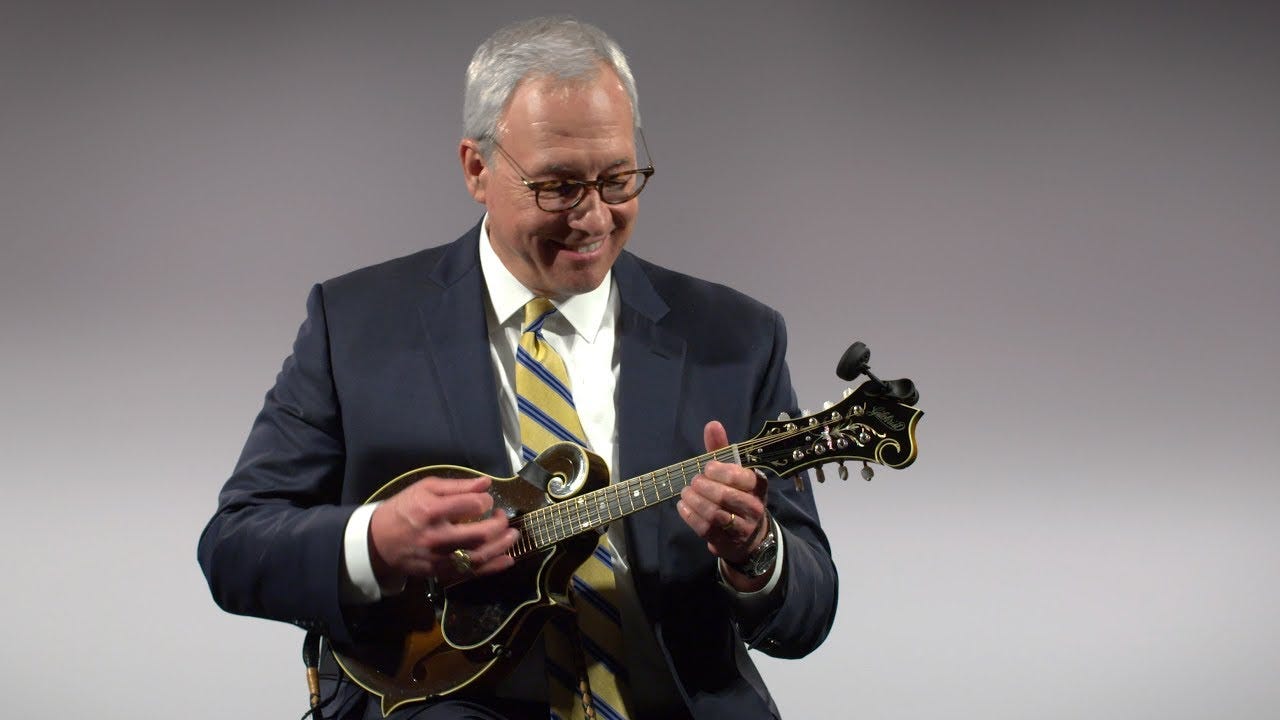

Thus, in the fall of 2022, the hardline conservative faction controlling the university board tried to oust Pettit—guilty of the heinous crime of being very slightly less conservative than the board—and send him back to his prior career as an itinerant evangelist who traveled with a Christian bluegrass band.

But the board’s action sparked an unprecedented backlash—for BJU, at least—from an ad hoc alumni group organized on Facebook. (A platform which, ironically, was blocked on campus when I was a student because it might expose us to worldly influences. Like hydrofoiling, presumably.) Under pressure, the board backed off and renewed Pettit’s contract; but it then spent the next several months undermining his leadership, leading to Pettit signing a letter of resignation this April.

However, the resultant second wave of alumni outrage has since led the hardliner board chairman to resign, leaving the school in a state of limbo as to who next gets the unenviable job of wrangling this particularly bitey nest of squirrels in exchange for a high future risk of severe reputational damage and the incredibly low (for a university president) salary of $150,000.

Those are the facts of the matter, but they are insuffiencient for truly understanding this moment. It has deeper structural and historical roots, seeds sown nearly a century ago at the founding of Bob Jones College that are now bearing strange fruit at a post-Bob Jones University.

If you stop and think about it, it’s less surprising that a fundamentalist college would put a stop to a fashion show than that such a place hosted a student fashion show in the first place. In a way, it’s as unexpected as it would be for Vogue to do a cover shoot of Franklin Graham. (Someone fire up Midjourney, asap!) The worlds of high fashion and fundamentalist higher education do not often overlap.

And that leads us to a fundamental tension at the heart of BJU fundamentalism. At its founding in 1927, the eponymous Bob Jones Sr. was determined to establish a liberal arts college, not just another bible training institute like Biola or Moody Bible. Certainly, the school would train preachers, missionaries, and bible teachers, but all students would also learn literature, history, drama, art, and be offered free music lessons.

This was a product of founder Bob Jones Sr.’s upbringing in rural poverty on the wiregrass frontier of Alabama. When he entered what is now Birmingham-Southern College, he caught a glimpse of the way college education could open a door to middle class status and social respectability. (Also important was his second marriage to Mary Gaston Stollenwerck, who came from old, southern money.) Yet he was increasingly concerned about secular colleges creating “shipwrecks” of faith out of Christian students. So he wanted a school that would combine intellectual rigor in the humanities with orthodox Christian doctrine taught in Bible classes and preached from a “hot” chapel platform.

Bob Jones University would instill Victorian social norms and advance a culture of bourgeois aspirationalism. Remember, in the late-19th and early 20th centuries, moral self-improvement was à la mode — urban clerks scribbling away in journals, mass attendance at educational lectures on the lyceum circuit and in Chautauqua tents, door-to-door encyclopedia salesmen—and Bob Jones University would give that impulse a sacralized spin.

Certainly, while I was there, the highest aspiration of a Bob Jones University student was to be considered a “renaissance man,” someone who combined religious ardor with scholastic aptitude, physical fitness, and artistic and dramatic finesse. Students who excelled only in one venue—jocks, art kids, etc—were encouraged to branch out and become more well-rounded.

This led to odd juxtapositions. Fraternities and sororities were banned, but all students were required to join literary societies. Most popular music was prohibited, but all students had to attend annual operas and orchestra concerts. Going to the movies was not allowed, but attendance at Shakespearean plays—often featuring the Bob Joneses themselves—was mandatory, and the university would eventually start its own movie-studio to produce epic period pieces. (Easter Egg: you can spot a very young Paul Matzko for approximately 0.3 seconds in the corner of a crowd shot in this movie about the Soviet persecution of Russian Baptists.)

Under Jones III, the school began hosting a tableau vivant called “living gallery,” a once popular Victorian era entertainment all but eradicated by the rise of film. Anti-Catholicism was an ordinary topic of chapel messages, yet the university owns the largest collection of Baroque religious art outside of the Vatican, with a particular focus on the Old Masters and Counter-Reformational paintings!

In a way, Jones Sr. replicated his own experience of college while setting up BJU, which was then mostly frozen in amber until the 21st century. BJU’s emphasis on education in the norms and rituals of Victorian polite society continued long after most other schools evolved into their current, more relaxed modes. Sunday afternoon vespers—think of choirs in gowns with grand musical accompaniment—were a weekly event. Societies sponsored annual formals.

Students were encouraged to take dates to all university functions. There was a literal dating parlor—though we called it the “land of couches”—where students could get not-too-cozy under the eye of spinster chaperones. It’s straight out of a novel about southern finishing schools or inter-war colleges! Just imagine trying to mandate that every student at, say, Pennsylvania State University get dressed up in formal attire, attend a three hour Verdi opera, and do it sober. The mind boggles.

But placing cultural education on the same plane as religious education was always controversial in fundamentalist circles. For example, while opera has a staid, stuffy reputation today, in the early 20th century it still retained some of its older reputation for cosmopolitan worldliness and sensuality. Wheaton College—which now fashions itself as “the Harvard of Christian schools”—was then locked in a competition with the newer Bob Jones College for fundamentalist supremacy. Wheaton’s arch-conservative president in the 1930s, J. Oliver Buswell, told parents of prospective students that the fact that Bob Jones College put on plays and operas was evidence that the Joneses were leading young people “into a worldly life of sin.”

BJU walked an uneasy middle ground when it came to cultural engagement. Typically, artifacts of low and popular culture (from jazz to Hollywood) were scorned while high culture, at least that of the late Victorian era, was considered a necessary pursuit for the man or woman of God.

During the mid-20th century, a new branch was spliced onto the older Victorian trunk: a counter-counter-cultural backlash. The “Jesus People” were not welcome at BJU, and the school formalized strict rules targeted at keeping the longhair hippies out, eg. daily “hair checks” at chapel, no women in pants, no contemporary christian music, and so on. Sometimes, that meant going to truly ludicrous lengths, like when the campus chief of police applied for a machine gun permit in order to deter any potential anti-Vietnam war protestors from invading the campus. But even the small, silly rules took on totemic significance because they acted as a buffer against the intrusion of dangerous, worldly values and outsiders.

In the early 21st century, these latent tensions were still thick on the ground. You could get whiplash, one moment listening to sermonizing about the incipient dangers of worldliness—the sinful spirit of κόσμος lying in wait—and then seeing, emblazoned over a classroom chalk board, a popular saying of Bob Jones Sr.: “There is no difference between the secular and the sacred; all ground is holy ground, every bush a burning bush.” All truth is God’s truth…except if it comes unshaven, unshorn, or with a little too much funk.

That tension was never fully resolved, except perhaps in the personalities of the Jones family itself. For decades, upon entering the campus administration building, you would be confronted with a painting of Bob Jones Jr. dressed in the regalia of Shylock from the Merchant of Venice. The personal charisma and extensive connections the family maintained within a broad network of fundamentalist churches gave the school leeway when it came to (mildly) pushing the envelop for a (limited) fundamentalist cultural engagement.

Given that context, it’s not surprising that BJU would both host a student fashion show and then face a backlash for doing so. The university hasn’t been led by a Jones family member—the last was Stephen Jones: first of his name, fourth of his line—for a decade. Finding the story of the gospel through renaissance era fashion would have been second nature for this guy:

But the Jones family’s cult of personality has long since worn thin, and in an era when Fox News has a bigger pulpit than any church, a man in fancy dress no longer reads as the image of an urbane, renaissance man-of-letters that the Jones family once cultivated.

Indeed, ex-president Bob Jones III has joined the hardliners, complaining that the school has “veered” from its “unique distinctives.” It can be hard to parse what’s so distinct about the absolute hodgepodge of hardline accusations; they’re either worried about a vague-but-severe theological drift at BJU, concerned about changing gender norms (a la female athletes wearing shorts), or are reacting to shifting class expectations (staging a Disney musical instead of an opera).

There’s a brittleness to the response that’s partly a function of how antiquated this combination of cultural impulses has become. A high/low cultural distinction rooted in late Victorian social norms and expressed via bourgeois aspirationalism was then partially, although not fully, overwritten with conservative anxieties from the 1950s/60s, and then preserved for half a century as the school adopted a bunker mentality towards the outside world.

That bunker mentality was propelled in part by white massive resistance to desegregation. That subject deserves its own, fuller treatment and so is a topic for another day (though oh my, I can promise you some stories!). Setting that aside for the moment, the school’s multi-decade decline can be traced back to its appearance before the US Supreme Court with Bob Jones University v. United States (1983), when the school decided to stake the flag of religious liberty on its right to racially discriminate. It was one of the most dunderheaded choices in the history of Christian higher education. BJU was now a non-accredited, non-tax exempt university with a national reputation for sacralized racism. It’s no wonder that student enrollment steadily dropped through the 1980s, 90s, and 00s.

Were it not for the rise of the Christian homeschooling movement, Bob Jones University might have closed down then. But by selling to homeschoolers looking for conservative curricula, the BJU Press turned into a cash cow—producing textbooks, video tapes, and, later, in-home satellite courses—and bailed out the otherwise tuition-dependent university. That remains true today, although the for-profit functions have been divvied off into a separate entity that continues to cross-subsidize campus operations.

But by the late 00s, the school was beginning to reach the outer limits of its experiment with whether becoming a press with a vestigial university attached was a sustainable proposition. Student enrollment had gone from decline to rout. The university’s mishandling of sexual abuse allegations made national headlines, a fundamentalist canary in a pre-Me Too coal mine. The last Jones was eased out as the university board jonesed for a fresh face.

It found it in Steve Pettit. In one sense, Pettit was reminiscent of the first Bob Jones: both itinerant evangelists who crossed denominational lines to hold week-long revival meetings replete with musical accompaniment—from Homer Rodeheaver’s trombone to Pettit’s mandolin. Jones had always been a prodigious fundraiser; and in short order, Pettit proved to be apt in that regard himself, shoring up university finances while pulling on his informal network of churches to bolster student enrollment. But the university’s finances are still such that, as a former board member noted, even a sustained, 10% decline in student enrollment could be enough to bankrupt the university.

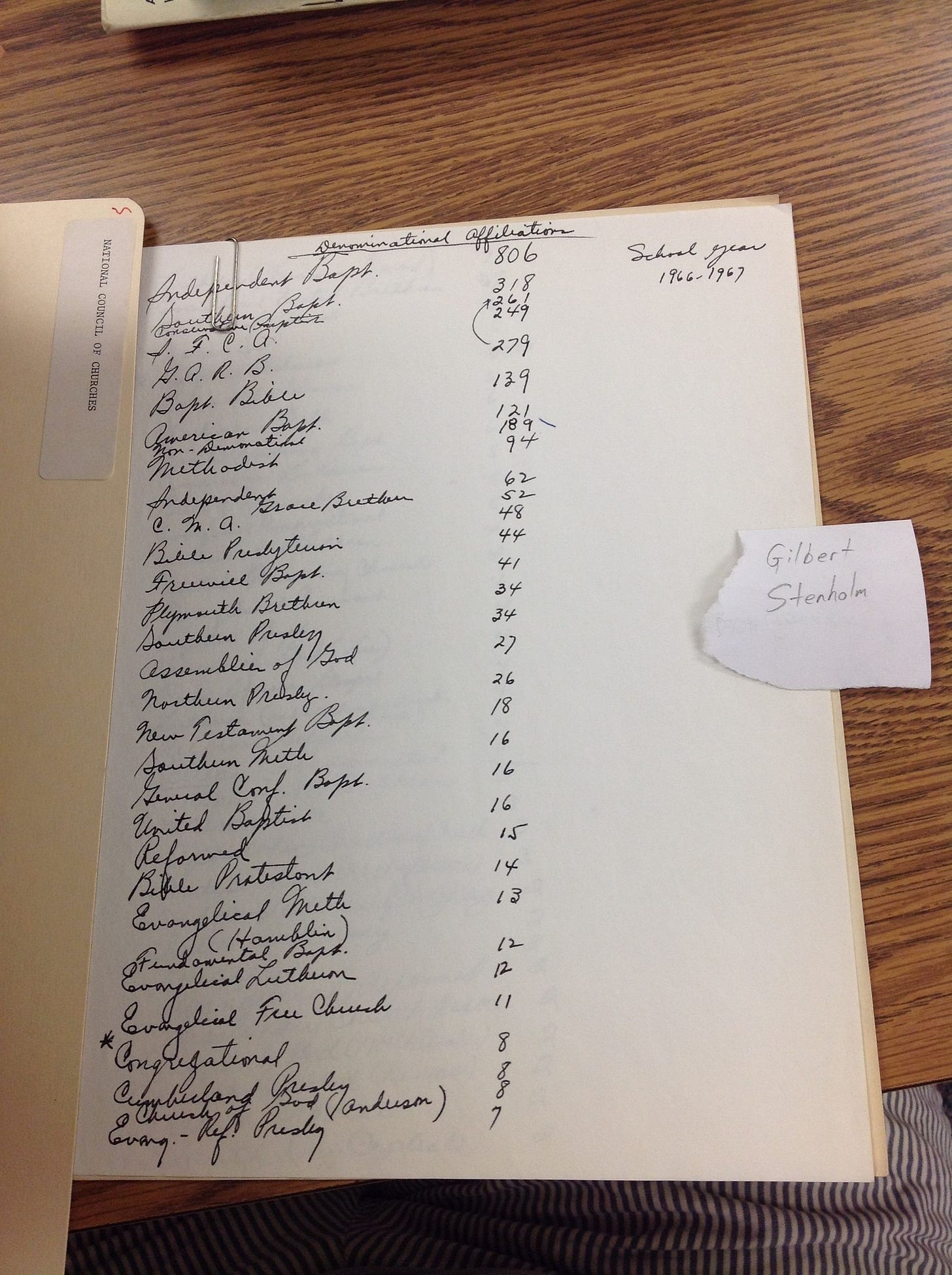

Yet the ways in which Pettit was most like Jones were also the attributes that most alienated hardline conservatives. That was in part because the university—which had always prided itself on being non-denominational as a matter of big tent fundamentalist principle—had become dominated by students coming from independent fundamental Baptist (IFB) churches.

This represented quite a change from the old days, when the studentbody was more denominationally diverse. Jones Sr. himself had come from Methodist and Primitive Baptist stock, neither of which send many students to BJU today. In 1946, Bob Jones College awarded an honorary doctorate to J. Roswell Flower, one of the founders of the Assemblies of God, a denomination that continued to have meaningful representation at the school as late as the 1960s. (It’s all but impossible to imagine pentecostals at BJU today!) Below, you can see a partial list of the studentbody’s denominational affiliations from ‘66-67; it’s heavy on—but non-exclusively—Baptists, with more denominational Baptists than non-denominational.

Indeed, the fact that the denomination with the second largest student contingent was the Southern Baptist Convention is interesting given that Steve Pettit’s willingness to reach out to local Southern Baptist churches was proffered by the hardliners as proof of his theological compromise. (And this despite the SBC being more consistently conservative today than it was in the 1960s.) But in this regard, Pettit was truly following in the footsteps of Bob Jones Sr., who expressly organized his school on non-denominational grounds with a barebones creedal statement.

IFB dominance wasn’t confined to the studentbody; the university board was also mostly IFB. The chairman of the board and the hardline faction leader, John Lewis, is a retired pastor of IFB churches in Guam and Michigan. Indeed, the Michigan connection—shared by other hardline board members including Hantz Bernard, who was recently forced out along with Lewis—is no accident.

For decades, Michigan was the number two state of origin for Bob Jones students (after South Carolina), which is a lingering artifact of the mass exodus of Michigan Baptists from the Northern Baptist Convention in 1932. That history means that the various associations of Baptists in the old northwest states (especially MI, WI, & MN) are independent in structure but also better organized relative to more isolated Baptist churches elsewhere in the country; and they thus exert an outsized influence on fundamentalist discourse and factional politics.

In any case, the lack of formal denominationalism means that fundamentalist disputes tend to get particularly messy. In a standard religious denomination, there are structures for resolving factional disputes, ie district hearings, synod rulings, systems of appeal, etc. But while BJU operates as a quasi-denominational subsitute—inasmuch as it provides some of the services of a denomination (clerical training, annual conferences, a sense of shared identity)—it has none of structures for channeling disagreements.

As a result, when fundamentalist infighting spills out into the public it can turn into a general popularity contest in which increasingly vicious rumors and accusations are the currency. Victory comes by ruining the public image of the targeted party. This is where the heightened rhetoric of l’affair de Pettit comes from. For the hardliners, it wasn’t enough that his vision for the university was flawed, no. It must be theological compromise of the highest order!

Ironically, the structural changes that enabled a board revolt against Pettit were a result of reforms pushed by Pettit himself. The school had always had a strange leadership structure. The school had been organized along the lines of a New South mill town, a place in which everything was owned and operated by the company. It was a near total corporate welfare loop: one could be born in the university hospital on one of the most comprehensive healthcare plans outside of the VA; schooling was free (but compulsory) for faculty children; there was subsidized on-campus housing; attendance at Sunday morning “church” services was mandatory; and the university operated a radio station, dairy farm, and retirement home. In exchange, staff salaries were low, exit rare, and loyalty expected.

But while it may have been a company town in structure, it was a family business. The Joneses exercised near total control over the university day-to-day, messaging, and policy. The board as it then existed was large, unwieldy, and packed with family friends and professional acquaintances, turning it into a rubber stamp for the wishes of the Joneses.

That changed with Pettit’s push for regional accreditation, one of the requirements of which was a streamlining of the board. The size of the board was pared back, making it a more efficient body, but the powers of the board, and especially the board chairman and the executive committee, were not simultaneously reformed. Functionally, this meant that a fraction of the total board—just six members on the executive committee—has the power to unilaterally change board rules, and the chairman possesses an unparalleled power to make board appointments without executive input.

So when the hardliners under Lewis decided to oust Pettit in 2022, they were able to stealthily change the rules to require a supermajority of the executive committee to approve any renewal of Pettit’s contract. This act of hardliner minority rule kicked off the next six months of drama.

At this point, I hope you can see how the backstory of the student fashion show that brought down a university president is as interesting as the event itself. It brings into sight a century’s worth of cultural change and class contest. The aspirations and fears of fundamentalists past continue to haunt those who remain at what truly is the world’s most unusual university.

Thank you Paul for articulating a culture I understand at a visceral level.

BJU is certainly a dichotomy. But life is a dichotomy. My father grew up a Kansas Reformed Presbyterian where barn dances on Saturday nights were followed by solemn Sunday services singing the Psalms with no instruments.

That Kansas boy would meet a Pennsylvania Dutch Methodist girl in an EUB Sunday School class on a late 50s BJU campus. Almost sounds humorous!

That couple would go on to teach in the public school system, help a struggling IFB church school in NC, go to Guam for a couple of years working for John Lewis. Later dad went to work for BJU Press as the mid US rep.

All that to say this, I get it. Cultures die hard, especially one of a religious nature. When practice becomes routine and routine becomes the norm and the norm becomes sacred, expect there to be resistance to change.

I attended in the mid 80s and my daughter just a couple of years ago. I once told dad, the BJU you attended is NOT the BJU I attended. When we took our daughter there, during Steve Pettit’s administration, it too was vastly different from my experience. I was truly jealous. Faculty, staff and students all seemed genuinely happy and had great spirits. I knew nothing of evangelist Pettit but felt it made sense having someone of his experience leading the institution. A BJU Bluegrass Band? . . Now that is weird. . . But I LOVE Bluegrass music! I did get to sit next to Dr. Pettit at dinner and talk about our mandolins, yes the same one my grandad used at the barn dance!

It took me years to overcome a bitterness that my BJU experience was not that of my parents. Maturity has give a perspective that we live in a fallen world surrounded by fallen people. What a shock the day I learned my favorite Bible characters all had a dark streak and needed redemption!

God’s work was accomplished prior to the existence of the university and will certainly be accomplished long after the campus is shuttered. I just hope that doesn’t happen in my lifetime. There is a new generation of young people that would benefit from a BJU education.

I stumbled across your article finding it interesting,having myself attended BJU (1974-1980, BA, MA). You analyzed in an intriguing manner the struggle between trying to be a cultured institution of higher learning while attempting to please hard-line fundamentalists. When I tell people where I went to college, I never know which aspect they are familiar with. I was involved in the music department, playing in the Trombone Choir in undergrad, and singing in the Concert Choral during grad school. I studied both the trombone and voice with professors. But, I was a 'preacher boy,' so it was interesting being a part of both of those worlds. I remember that as a trombonist, we would have been shamed for playing in any style that could be remotely reminiscent of Jazz, and there are many legendary jazz trombonists (I had fallen in love with Jazz during high school). So, I was intrigued when hearing the piano students practicing the music of Scott Joplin as I passed by the practice rooms. I have since learned that Joplin is considered by many to be the "Father of Jazz." It seemed to be that if someone in the administration (usually one of the Jones's) OK-ed something, then it was fine. I remember noticing the statues in the amphitorium, women holding up something, maybe lamps, (I was after all an adolescent boy) were adorned in such a manner that, let's just say, any female student wearing those clothes,or the lack thereof would earn a trip to the dean of women's office, or maybe worse.

I have written a memoir about my religious journey that includes my years at BJU and some years following as I found my way out of the indoctrination that I absorbed there. The book is not a critique of BJU, in fact I give credit where it is due to dedicated faculty and aspects that were good for me. But I do describe the racism that I encountered there. The book covers my life starting years before BJU and for some years after, chronicling my religious journey that put me in the ministry for nearly 30 years (including being a foreign missionary for 7 years, then later becoming a psychotherapist for the last 21 years. If you or your readers are interested, my book is "THE LONG SURRENDER: A Memoir About Losing My Religion" by Brian Rush McDonald. The BJU faithful view me as a heretic, but you might find it intresting. You can find in on Amazon or I would be happy to provide a copy for any interested readers. brianmcd74@gmail.com