This is the most influential chart of 2024 thus far.

It comes from a December report by the National Contagion Research Institute (NCRI), titled, “A Tik-Tok-ing Timebomb,” which alleges that TikTok has been manipulating its algorithm in the United States to advance the interests of the Communist Chinese Party.

It certainly looks damning. After all, can you think of a non-sinister reason for the highly skewed hashtag ratios between Instagram and TikTok? There are 181.1 times more hashtagged videos on the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests and 81.5 times more videos about Tiananmen Square on Instagram than on TikTok. Such a skew has got to be a result of TikTok skewing the algorithm to cover up China’s bad behavior, right?

Many have assumed so. The report received wide news coverage and it swayed influential pundits. Senator Ted Cruz brought it up in a hearing with TikTok CEO Shou Chew, referencing the data on this chart in particular. That attention has turned into action; the NCRI report fueled the latest push in Congress to have TikTok banned or divested from its Chinese ownership.

There’s just one problem. The chart doesn’t show what people think it shows. And the report it is drawn from is profoundly flawed. While the report is based on real data from TikTok and Instagram, nearly every aspect of how the data was gathered, analyzed, and presented was based on a series of faulty assumptions.

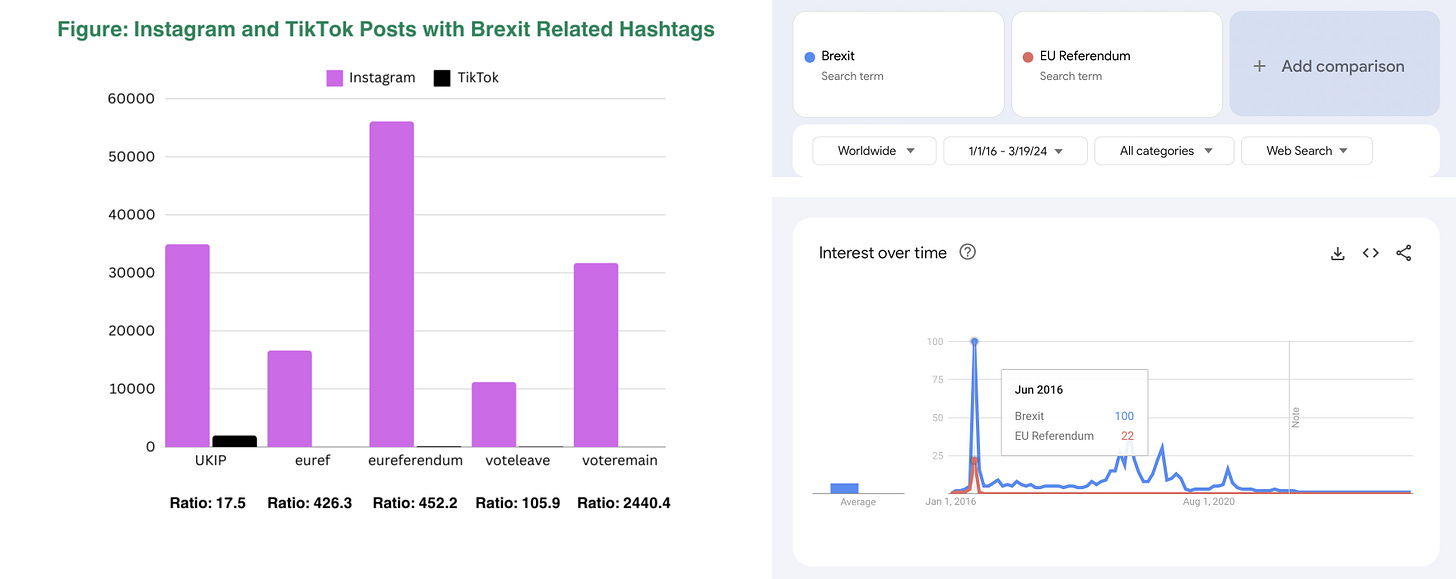

To illustrate how that is so, here’s another chart showing the hashtag distribution for a different hot button topic with immense geopolitical significance. Take a guess at which act of Chinese maleficence it shows.

It’s a trick question. I made this chart — it’s not from the report — and it shows the distribution of videos on Instagram and TikTok for hashtags related to Brexit, in particular the 2016 vote. China was neither involved in the great divorce of the United Kingdom from the European Union nor did Chinese authorities adopt an official position on the question. In other words, the wildly skewed ratios for Brexit hashtags – some of which are 10x larger than the ratios from the first chart! – are unlikely to be the product of Chinese manipulation of the TikTok algorithm.

But if we cannot blame a sinister communist conspiracy, how can we explain these large divergences in the ratios? The answers are rather mundane. There are seven core failures in the design of the NCRI report that could explain most or even all of the skew in the ratios.

#1. Failure to Account for Platform Existence

Instagram was launched in 2010 and TikTok in 2017, so there is a mismatch in the hashtag data collection window.

It is simple to find how many videos on Instagram and TikTok have used any given hashtag. Both platforms have a dedicated /tag url, so researchers can input a hashtag and get the total number of the posts/videos that have ever used that hashtag. There’s just one problem. If the goal is to figure out whether TikTok is manipulating the algorithm, we want to know the relative frequency of hashtag use, not the absolute number of uses.

Comparing two absolute numbers will introduce a skewed ratio because Instagram has existed twice as long as TikTok: Instagram was released in 2010 while TikTok launched in 2017. Which means Instagram has almost exactly twice as long a data collection period as Tiktok. All things being equal, we should expect that simple fact to increase the skewed ratio by a factor of two, in particular when comparing durable topics that have been of interest since 2010.

The NCRI report failed to factor platform existence into its ratio, but if you look closely at the NCRI report, you can still see subtle signs of this distortion. For instance, the report’s list of pop culture related hashtags includes three related to the Grand Theft Auto video games. The most durable hashtag – #GTA, which would be used to refer to any game in the long running series – has nearly double the ratio skew (1.9x vs 1.0x) of the hashtag linked to the upcoming game, #GTA6.

As a rule of thumb, if the topic being hashtagged was relevant prior to 2017, the ratio should be adjusted down by as much as half to reflect the simple fact that TikTok did not exist before 2017.

#2. Failure to Account for Regional Availability

TikTok has been banned in multiple countries, further reducing the hashtag data collection window in key regional markets.

Yet it’s a generalization to say that Instagram has been around for twice as long as TikTok. In specific national markets, TikTok has been banned while Instagram has remained available. For instance, Hong Kong banned TikTok in 2020 during the mass pro-democracy protests. Which means that TikTok was only available in Hong Kong for a little under three years (2017-2020) compared to Instagram’s 14 year run there.

And we would expect the skewed ratio in those places to be wider given the even narrower window for TikTok data collection. TikTok existed in Hong Kong for roughly a fourth to a fifth as long as Instagram has – and Hong Kong is an English-speaking city – so we should reduce the ratio by a compensating amount, as much as 5x. And if we reduce the ratio for #HongKongProtest(s) by a factor of 5x, that would reduce the skew from 181.1x to a much less alarming although still elevated 36.2x.

There’s another country where TikTok has been banned since 2020 even as Instagram remains popular: India, which has the second largest number of English-speakers in the world. (Remember, these are English-language hashtags.) India and China also have a long history of national animosity, especially in regards to Tibet. These facts would lead us to expect a major, albeit hard to quantify, contribution to the skewed hashtag ratio as English-speaking Indians post videos critical of China’s imperial expansion on Instagram but have limited access to TikTok.

#3. Failure to Account for Topicality

Public interest in hot button issues is variable, which can even more heavily skew hashtag ratios for topics that predate the launch of TikTok in 2017 (or postdate its ban in key regional markets).

But simply comparing platform existence and regional availability is overly mechanistic. Public interest in current events isn’t smooth or constant. Likewise, the use of hashtags ebbs and flows as topics wax and wane in the public consciousness. This has a heightening effect on failures #1 and #2. If the hashtag refers to a particular protest movement that occurred at a moment when TikTok did not exist but Instagram did, then the resulting ratio can easily become hugely unbalanced.

This is what my chart of Brexit related hashtags shows (below left). Although the Brexit question has been a topic of international interest for nearly a decade, the actual vote to leave the European Union happened in 2016, which is before TikTok existed. And as you would expect, the more event-specific the hashtag – such as #euref & #eureferendum – the more highly skewed the ratio (426.3x & 452.2x). By contrast, the more durable the hashtag the lower the skew, as with references to the political party #UKIP (17.5x) and #Brexit itself (6.3x).

This corresponds nicely with the Google Trends data (above right). While the spike of public interest in Brexit in 2016 skewed all hashtags, it is more pronounced for the actual EU referendum than for more generic hashtags also used during Brexit implementation.

Failures #1-3 taken altogether potentially explains much or even all of the skew in the NCRI’s results for multiple topics. For example, we can see from Google Trends data that US public interest in the South China Sea and Tibet both peaked in 2016 prior to the existence of TikTok. If topicality can explain ratios on the order of 452.2x (#eureferendum), then ratios as small as 48.8x (#FreeTibet) and 20.6x (#SouthChinaSea) are entirely unsurprising.

Topicality also explains some of the hashtag skew around the Hong Kong protests, albeit not to the same extent as it does for Tibet or the South China Sea. That’s because while international interest in the Hong Kong crackdown peaked during the 2019-2020 pro-democracy protests, the first wave of mass protests actually occurred in 2014, back when TikTok did not exist. Likewise, the protests were still ongoing when TikTok was banned in Hong Kong during the summer of 2020 – just as the platform exploded in popularity during the pandemic – further skewing the results.

#4. Failure to Establish a Reliable Baseline

Always ask, “Compared to what?” The NCRI compares Chinese foreign policy interests to Taylor Swift rather than something more topically appropriate.

There is no inherent reason why two, discrete platforms with different primary formats (photo vs video) and a different set of use cases must naturally have a one to one ratio. The NCRI report recognizes this fact and so offers a long list of hashtags about politics and pop culture in the United States as a baseline, from Taylor Swift to Donald Trump. This yields an average ratio of between 2.2x - 2.6x.

But that baseline rests on a questionable assumption. After all, there are roughly four times more English-speakers in the rest of the world than those that live in the United States, not all of whom share the same set of views, interests, and app preferences. It is a leap to assume that domestic US topics are the correct baseline against which to compare hot button international topics.

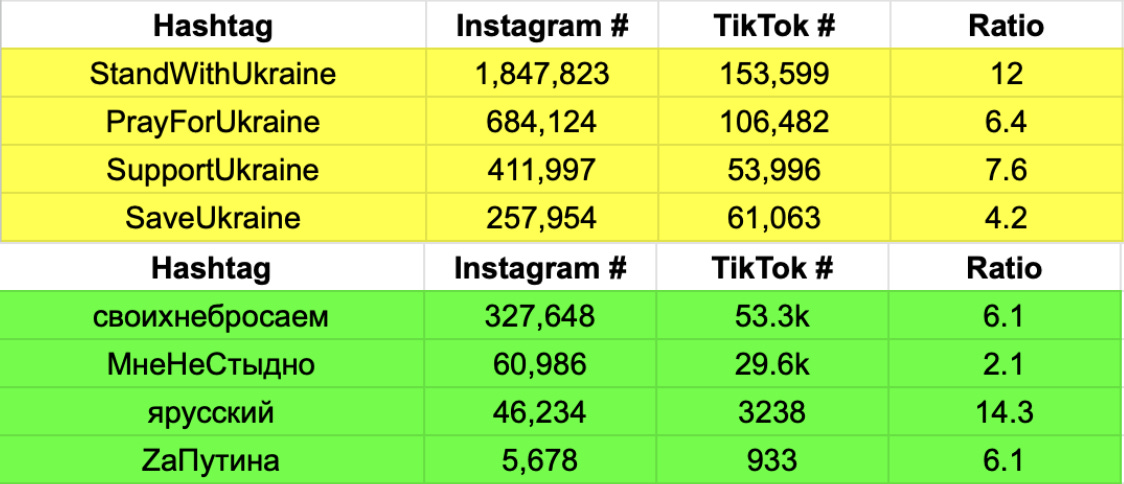

Ideally, in order to detect platform specific bias we would want to compare hashtags from both sides of a controversial topic. The NCRI only fitfully does so, usually providing only hashtags from the side of the issue that runs against Chinese interests. For example, below in the yellow highlighting is the NCRI’s list of pro-Ukrainian hashtags (a conflict in which China is generally understood to be unofficially pro-Russian).

As long as we assume the proper baseline for the Ukraine conflict is Taylor Swift et al, then these ratios appear to show a suspicious skew, which is then taken as implicit evidence of China manipulating the TikTok algorithm in favor of Russia. But now compare the NCRI’s list of pro-Ukrainian hashtags to the green highlighted list above that I created of the most popular pro-Russian hashtags (which, translated, mean things like “I am not ashamed” or “We don’t leave ours behind”).

The ratios are quite similar. If China is supposed to be manipulating the TikTok algorithm to help Russia, it does not appear to be doing a very competent job of it!

(Note: When getting hashtag results via direct URL, TikTok rounds the larger numbers and Instagram does not. I kept the ‘k’ for thousands and ‘m’ for millions to make it apparent when that’s the case.)

But even in situations where it’s hard to identify “pro-China” hashtags as a contrast, there are alternatives to relying on domestic US pop culture and politics for a benchmark. For example, given how many of the topics from the report are related to geographical locations and cities – ie, Hong Kong, Tibet, Taiwan, Tiananmen Square – I compiled my own list below of global city hashtags as an alternative baseline.

The average ratio between Instagram and TikTok for these cities is 19.2x, which seems like a better proxy for hashtag use related to locations than hashtags about a pop star or American president. The reason for this location-based skew is entirely non-sinister. Instagram has long been the preferred platform for photographers, tourists, and jet-hopping travelers abroad to post photos of their morning coffee in Santorini or a temple in Delhi.

Inasmuch as 19.2x is a better baseline for comparing hashtag use in an international context, then the ratio of many of the topics listed in the NCRI report are far less alarming by comparison. For example, while Tiananmen Square can be used as a shorthand reference to the 1989 massacre of protesting students, it is also a popular stop for international and local tourists. It makes a major difference whether we compare #TiananmenSquare (ratio: 56.6x) with a baseline derived from Taylor Swift and other domestic topics (ratio: 2.2x - 2.6x) or a baseline composed of other global tourist destinations (ratio: 19.2x). That would functionally reduce the skew above expectations for #TiananmenSquare to a decidedly less dramatic ~3x.

#5. Failure to Fully Account for Audience Size

Instagram has more users than TikTok, which skews the number of hashtags used.

All things being equal, having more users for a platform will mean a higher number of posts using any given hashtag. Instagram remains a significantly bigger platform than TikTok, with roughly 1.5x as many users in 2023. The NCRI report does briefly acknowledge this fact, estimating that there should be 1.5x - 2.0x more hashtags on Instagram because of the larger user base. (The NCRI report does not, however, factor this observation into its ratio formula.)

But that underestimates the effect of audience size on relative hashtag use for a simple reason. The number of Instagram and TikTok users is not constant. While Instagram has 1.5x more users than TikTok today and had 2.0x more in 2020, that differential was 4.0x in 2018. The older the topic, the more skewed the effect of the relative size of the user bases on the hashtag ratio.

Were audience size properly factored into the ratio formula, it would reduce the hashtag skew across the board by a minimum of 1.5x - 4.0x.

#6. Failure to Account for Natural Variance

Some amount of skew in hashtag use is normal and expected.

The final failure is the hardest to quantify because it reflects the way in which platform-specific factors can create a wide range of natural variance in the use of hashtags. It is likely a function of the prime mover effect. Imagine that you are among the first users to post a video on a hot button topic. Hashtags help others discover your content, but if you are the first, you won’t find much when you search for topically useful hashtags. So you invent your own, perhaps piggybacking off of an existing, generic hashtag.

At that point, the prime mover effect kicks in. The first poster must invent a hashtag convention. Every subsequent poster can either try to get a novel hashtag to catch on or pick a pre-existing hashtag that is more likely to maximize exposure because trending hashtags tend to attract more views and may even get an algorithmic boost. As a result, the happenstance of a prime mover poster can create platform-specific skews in ratios.

The effect of this natural variance can be significant. For instance, while the ratio for #FreePalestinePS favors Instagram 1.7x, that for #FreePalestinePS[heartemoji] is 0.1x. That’s likely a product of prime movers spontaneously inventing very slightly different hashtags which then took on a platform-specific momentum that has led to a net margin of 17x. Likewise, from the list of domestic US politics, two hashtags that both have positive valence for Trump’s presidential campaign – #MakeAmericaGreatAgain (ratio: 15.9x) & #Trump2024 (ratio: 0.6x) – have a net margin of 25.6x.

In the absence of a truly comprehensive hashtag dataset – which neither I nor the NCRI report have provided – it is vital to remember that natural platform variance can account for a meaningful amount of skew.

#7. Failure to Account for the Competition

Instagram’s use of its own algorithms could skew hashtag ratios, particularly in regards to the Israel - Palestine conflict.

The NCRI study implicitly assumes that Instagram is a constant against which to measure TikTok’s variable algorithm. But Instagram also engages in content moderation, which means using an algorithm to identify, remove, or shadowban offensive posts. And as of 2023, Instagram has added an algorithm to help users discover content.

In particular, there have been multiple media reports that Instagram adjusted its content moderation policies after the October 7th massacre, resulting in the mass removal of pro-Palestinian posts. As Human Rights Watch summarized, “The censorship of content related to Palestine on Instagram and Facebook is systemic and global. Meta’s inconsistent enforcement of its own policies led to the erroneous removal of content about Palestine.”

If so, then the skew towards posts supporting Palestine on TikTok vis-a-vis Instagram could be a product of Instagram’s own manipulation of its algorithms. From a statistical point of view, Instagram removing pro-Palestinian content would have the same effect on the ratios as TikTok downgrading pro-Israel content.

It should not simply be assumed that this much smaller skew is a product of TikTok’s policies rather than a consequence of Instagram’s policies.

Summary

Not every failure applies to each category of hashtags in the NCRI report, but none of them are fully free from the report’s flawed design. And these failures can stack atop one another, amplifying their distorting effects.

For example, analyzing the Hong Kong protest hashtags by the first five failures reveals how the effects can be mutually reinforcing.

#1. Platform Existence: Hong Kong’s autonomy was an issue prior to 2017, which is prior to the creation of TikTok.

#2. Regional availability: TikTok was banned in Hong Kong in mid-2020, meaning TikTok has existed there less than a quarter as long as has Instagram.

#3. Topicality: there were particular spikes for public interest in the Hong Kong protests in both 2014 and 2019-2020, heightening factors #1 & #2.

#4. Baseline: do we compare hashtags for the Hong Kong protests (181.1x) to hashtags for Hong Kong itself (35.7x) or to Taylor Swift et al (2.2x - 2.6x)?

#5. Audience Size: interest in the Hong Kong protests peaked in 2019-2020 when Instagram had between 2x and 4x more users than TikTok.

Considered as a whole, it means there is nothing inherently sinister about even a skew as large as 181.1x like that for hashtags related to the Hong Kong protests. As we’ve seen with Brexit, factors #1-3 combined can create skewed ratios in the hundreds or even thousands of times. Similarly, if the proper baseline for comparison is 35.7x, then it reduces that 181.1x ratio to a much less remarkable 5.1x skew between Instagram and TikTok, which could then be subject to further reductions because of audience size, natural variance, and platform specific content moderation policies.

Perhaps the best way of illustrating just how distorting these NCRI design flaws can be is if we focus on hashtags related to events that have fully happened post-2017. That removes factors #1-3 entirely, giving us at least a chronologically similar comparison (although factors #4-7 can still apply).

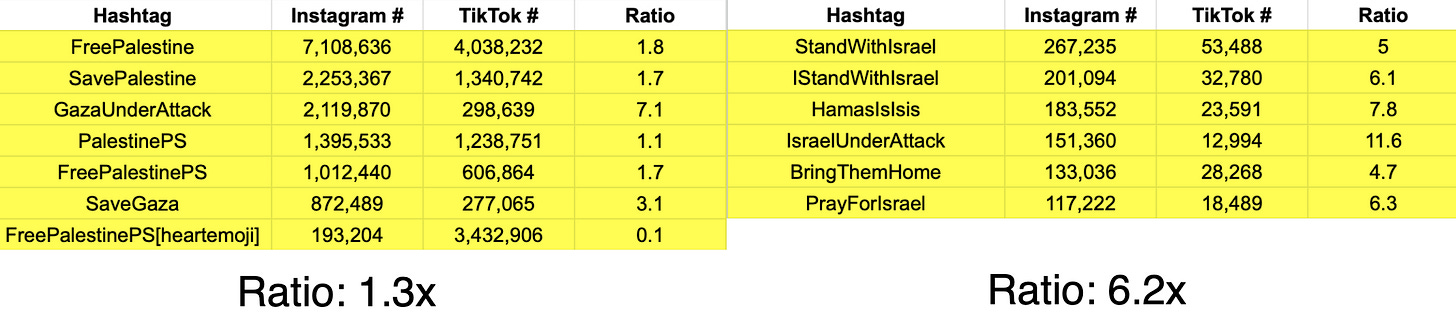

This is the case with the hashtags related to the Israel - Gaza conflict, most of which were either invented or popularized after the October 7th massacre and Israel’s invasion of Gaza.

The NCRI report’s data shows a skew of 1.3x for pro-Palestinian hashtags and 6.2x for pro-Israel ones. If we equalize the difference between them, we get 4.8x. If we further reduce that number by the fact that there are 1.5x more Instagram users than TikTok users, we get a ratio of 3.2x.

Now, certainly, that means there are roughly 3 times more videos using pro-Palestinian rather than pro-Israeli hashtags than we’d otherwise expect. (Although we don’t know if that’s a product of natural variance or even Instagram’s own content moderation policies as previously discussed.)

Regardless, if the NCRI report had led with a chart showing a 3.2x skew on Israel-Gaza hashtags, it is unlikely that it would have received the kind of widespread media and congressional attention that it did by foregrounding distorted ratios like 181.1x for the Hong Kong protests.

As a final note, none of this should be taken as evidence that China has not manipulated the TikTok algorithm. It means only that this particular NCRI report does not prove that China has manipulated the algorithm.

But given that government regulation of TikTok could affect the speech of 170 million American users, the burden of proof rests squarely on the shoulders of those supporting a ban. They must offer definitive and unambiguous proof. The NCRI report does not meet that standard.